War-Like Behaviors and Social Parallels in Ants

Nevertheless, he recognizes that to many minds the force of the facts, as seen in nature, is not readily put aside; and that the universal war habit of organized beings, as it appears to have existed in all time. seems to place upon a higher plane, as in harmony with natural laws, those war-like habits and acts that have dominated human history. This, at least, gives an exceptional interest to a study, for the sake of comparison, of the war methods of those lower orders of living beings whose social organizations strongly suggest our own.

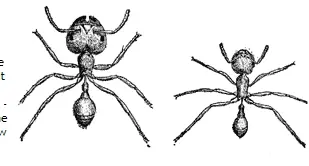

Among the foremost of these are ants, and ants, as an order, are war-like insects. The foragers carry their natural pugnacity into the field as isolated individuals, and show decided courage in the quest of food. Therein they are freebooters. Whatever falls in their way and they are able to possess, they take. This, as in the case of human brigands, often requires an appeal to force. An ant commune is as fair a scene of peaceful industry as a beehive; but everywhere in its vicinage "doth dogged war bristle his angry crest, and snarleth in the gentle eyes of peace."

This readiness for hostilities and ferocity in attack have been noted and recorded often of the hosts of true ants that swarm along the pathways of travellers in the tropics. For example, Stanley speaks of the "belligerent warriors" arnong the innumerable species of various colors that filled the African forests; of the "hot-water ants," as his men not inaptly named them, from the smarting pain of their stings; and of the minute red ants that everywhere covered the forest leaves and attacked his pioneers so viciously that their backs were soon blistered. These creatures doubtless acted from a principle of self-defence that led them to hurl their fighting myriads upon everything that crossed their way and disturbed their solitudes, though with no hostile intent. It was an act of natural belligerency, and no doubt was protective, in the aggregate, of life. It certainly seemed as little reasonable as were the unprovoked attacks of the human hordes of cannibal savages that assailed his expedition in their crowded boats, as he made his way through the heart of the Dark Continent, along the mighty Livingstone River. The tribes of ants and the tribes of men were not unlike in the native combativeness that animated them.